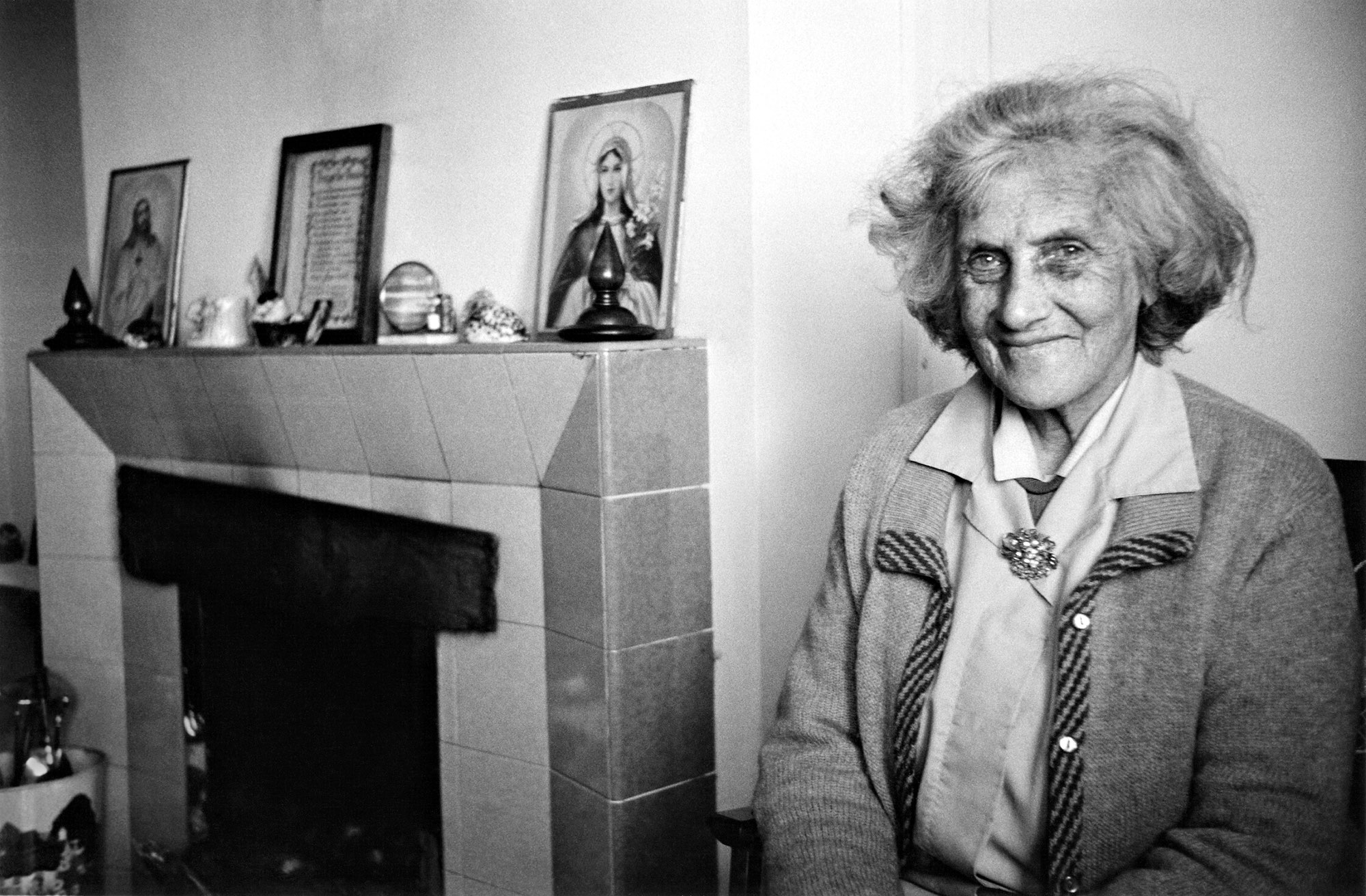

Sophie Louise, 2014

Paul Glazier’s Vatersay series is a collection of photographs taken on the Island of Vatersay—the southernmost and westernmost inhabited island in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland—across no less than 38 years. His forthright, black and white shots of rocky beaches and unfeigned faces tenderly map out the lives of several generations.

In celebration of close to four decades of capturing the life and spirit of Vatersay, we sat down together with the British Artist to revisit his body of work and discuss his relationship with the island.

For how long have you been working with Addie and Elliott Gallery, and how have these years been for you and your artistic practice?

“Our collaboration began somewhere in 2016 and I have felt very honoured to have had my work hanging between that of really exceptional photographers. For me, that’s been a wonderful morale booster (he laughs). Addie’s always been extremely encouraging of my work - she has a lot of faith in its quality and that's coming from someone who works with top artists. It's just been a privilege.”

In your book, Island Tides, you speak about aesthetics and how, in your painting practice, you aim to express beauty in different ways than simply reproducing reality as faithfully as possible. How does this aim translate in your photography?

“For me, it’s all really about expressing my perception of a place, my interaction with it and its people. It's about this relationship.

Of course, I do find it [his subject matter] beautiful, but I'm not actually seeking beauty. The beauty is… just there. It's about framing, allowing me to examine that sense of place or beauty, connecting what one sees in the outer world with the inner world. Photography gives me that opportunity. By framing, you are articulating a relationship in a certain way, interacting with it more than as a passive viewer. Releasing the shutter may sound like a very minimal interaction but it is, in fact, just part of an ongoing process. And that process is, to me, about the whole relationship, not just about that one shot, the construction of a second.”

Vatersay Village, c. 2017

Zoey at the Stove, 2014

Going back to the comparison between your photography and your painting—they’re of course very different art forms—, your drive in photography needs not be the same as in painting.

“Well, it's similar. With painting, I'm trying to raise a frame to an internal landscape. With photography, the landscape is an external one. But it's always about the relationship with the subject matter, whether a landscape or a portrait, painting or photograph.

As for reproducing reality faithfully, that's an idea I've always struggled with. I don't see myself as a documentary photographer. I don't believe there's an objective way of seeing the world, and ‘documentary’ implies a kind of objectivity. To attempt objectivity can be interesting, but I certainly don't want to impose myself on my subject matter. I am, of course, very happy that my Hebridean photography has a documentary element. I do think it's very valuable to capture an impression of a place and a time, for the future. It's nice to feel that it has a value in itself due to that historical aspect. Undoubtedly. But that's not really my drive. Rather, my focus is on articulating, for myself, and for others, my connection with the place and the people.”

In your book, you speak about photographing as a way to touch the world. What does the Vatersay series mean to you, and what narrative do you wish for these photographs to express to the world?

Toots, Catriona & Maggie, c. 1985

“My relationship with Vatersay has been very important to me from an early age, and photography has been one of the tools for me to examine that relationship.

Since the 80s I’ve been preoccupied with the idea of the nature of ‘home’. The feeling of belonging, the feeling of connection; the origin of these feelings and their constituents. For me, ‘home’ has very much been connecting with a still place within myself and at the same time finding its equivalent in the world.

As a teenager, I was very happy to have Vatersay as a holiday destination. At that age lots of things are going on internally, and for me the island became a safe space, a place of rest. It just felt more real and I could connect with it far more than I could with the London suburbs. Vatersay became a symbol of a place of quiet within myself, and has remained so.

Also, the people [of Vatersay] have always been important to me, and even more so as I've gotten older. I've seen children grow up, older generations die, new generations come up. And they’ve seen me grow up too. And that shared experience changes the whole dynamic of my relationship with the place.

Certainly, after my first show up on the islands back in 2010, I realised that particularly the portraits were very much appreciated by the people up there. In the 1990s and 2000s I'd really only been photographing landscapes, something which I now regret. But that show really encouraged me to also focus on the people again, because I could see how much that was valued. How people relate to a face is very different to how they relate to a landscape.

As for the narrative, there isn’t one, really. At least not in the linear or imposed sense. My Vatersay series arises out of my relationship with the place, and I don't like to steer it in a specific way, I prefer to let it evolve. I like to let it be what it wants to be.

I'd like the images to stand on their own for whoever looks at them, even if they've never been to the island. I would like the viewer to build their own narrative, relate to it in their own way, with their own memories.”

Nancy, Eilidh and Emily Rose, 2014

What has kept on drawing you back to the island in the last four decades?

“In the beginning, it was certainly getting that sense of peace and stillness that I needed. Later though, it was also about keeping in contact with friends. The island draws me back for the people, but also for that sense of grounding, of connecting with nature. It's a very sparse landscape. There are no trees. It's literally rocks, sky, grass and sea. So you do get a sense of something essential. Something beyond just postcard beauty.”

Hillside, 2016

This series also has and continues to become nostalgic and historical. As an artist, how do you feel about this?

“I think that’s become a very interesting aspect of the series. For the book, father John Paul wrote about how I'm leaving a legacy for the island. And that feels great. You know, most artists, myself included, are very busy with our own feelings, with trying to articulate certain things of our own. It's great to feel that this has value for other people. I think we all, in spite of our egotism, want our work to have value beyond ourselves. So when someone steps up and says ‘you've created a legacy for the island’, then I'm obviously very happy.

But at the end of the day, I just feel privileged to have had this connection over the years. I don't feel I've manufactured this apparent legacy. To me, these images feel like things that I've found — certainly my photographs, but also my paintings. They feel more like gifts that I like to share, and if they have value for other people, that's wonderful.”

After the Wedding, Castlebay, 2018

“The exhibition took place on an island not too far from Barra (Benbecula), but still quite a trip up nonetheless. A few of the islanders came especially for the show, which was great. All the reactions I've had have been extremely positive, not just for that exhibition, but also for the book. People seem very grateful, and it's been actually very moving. They've told me that it means a lot to them that someone has built a record of their lives, of a part of their lives. I haven't been up to the island since the book came out during the pandemic, so I'm curious to hear what the islanders think of it, what their impressions are.”

Pre-pandemic, the gallery co-curated an exhibition with Malcolm Dickson of Streetlevel Photoworks of this body of work in Scotland - what was the Vatersay islanders’ and the Scottish people’s response to this series?

Dawn Waters, on the Way to Barra Head, 2013

Sandy at Barra Head, 2013

Walking Down to Bishop’s Rock, 2013

This remote island community has undoubtedly played an important role in your life for so long. What is the future you envision with Vatersay, both artistically and personally?

“I'm sure I'll continue taking photographs there. I just am constantly inspired and engaged by the island. The more you look at something, the more you see. And the more you engage with something over a long period of time, the more you understand, or rather, the more you can feel that relationship and the better you can articulate it in terms of artistic practice.”

Vatersay Graveyard and Ben Rulibreck, 2016

Concluding, Paul, we would like to know what is your favourite photograph from this series?

“At this very moment, I would go back to what I originally wanted as the front cover of the book. It's the last photograph in the book, which is of Jennifer on the sofa of her grandparents, D.D. and Peggy. So that would've been 1985. In the back, through the net curtains, you can see the hills and the abandoned car. If you know my work, you know that I'm always looking through, looking through layers, which is also true of my painting.”

D.D.'s Grandaughter, c. 1985

Explore the beauty of Vatersay in Paul Glazier’s book, which paints a unique, dynamic portrait of the remote island and its community as time leaves its mark.

All photographs in this exhibition are available to purchase. Please contact Elliott Gallery for further information.